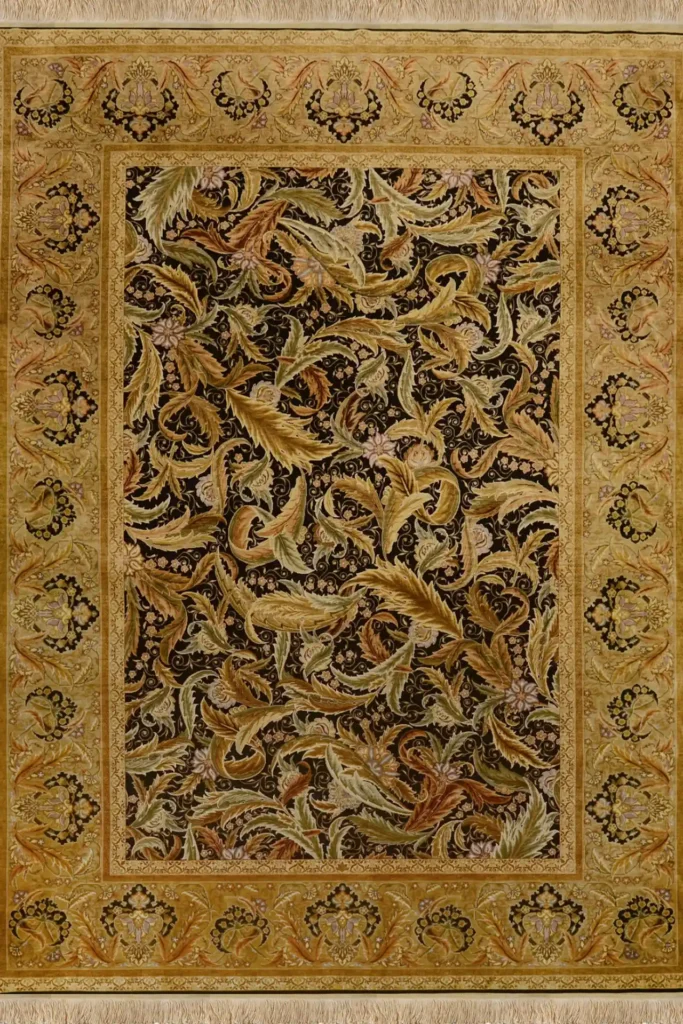

A carpet graces Çınar’s Emblem Collection, bearing the name Cordon. Inspiration flows from the saz style, a wild Ottoman flourish. At Çınar, the empire’s culture thrives thick with heritage.

Saz patterns anchor Ottoman nakkaş art, threading through caftans like vines. Şah Kulu, the maestro behind Saz Style, strutted the 16th century, heading the palace nakkaşhane under Suleiman the Magnificent. Baghdad birthed him, records say. Aga Mirek in Tabriz schooled him in paint and stitches, sharpening his gift. Archives from the Prime Ministry spill secrets: Şah Kulu’s name pops up among artists hauled from Tabriz to Amasya, then Istanbul after Yavuz Sultan Selim toppled Shah Ismail. A ledger from 1 Muharram 927—12 December 1520—shows him pocketing 22 akçe daily from royal coffers. By 952—1545—he climbed to serbölük of the Cemaat-i Rum nakkaşler, raking in 25 akçe a day until his last breath.

Forty-two years later, Şah Kulu toiled in the palace, churning out wonders. Documents hint at Suleiman’s generous nods—favors piled high, though he savored only a sliver. Nakkaşhane artists, under his watch, hoisted Ottoman decoration to its zenith in the century’s second half, fusing motifs into a singular groove. Şah Kulu tossed in big, curved, dagger-sharp leaves to the hatayi crew. Dense, tangled designs scream his signature.

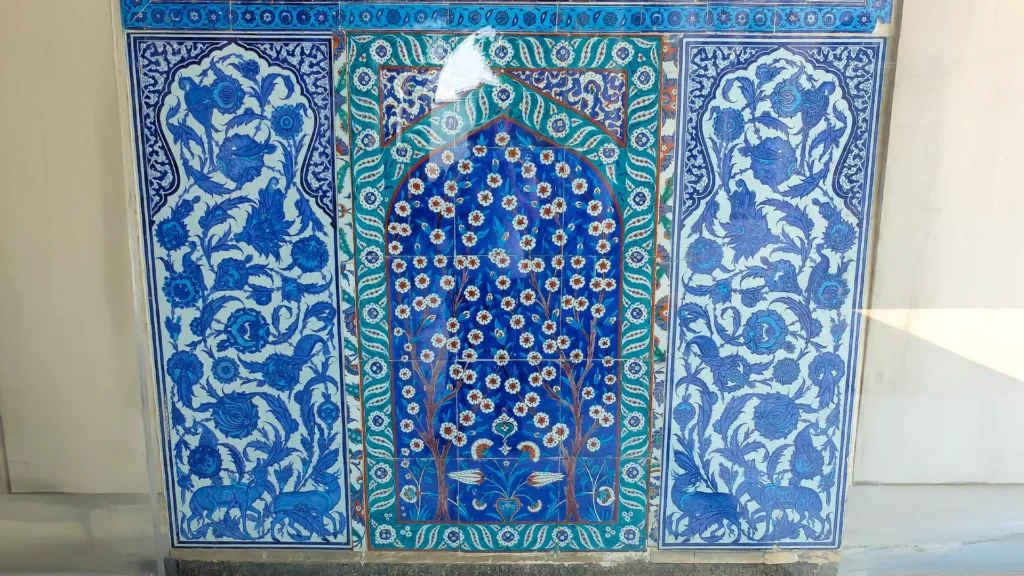

Ink-and-brush sketches from 14th-century Iran—Ilkhanate, Celayirli, Timurid, Turkmen—kickstarted the saz style. Şah Kulu grabbed it in the 16th, reworked it in the palace nakkaşhane, and passed it to his pupils. Illumination, tiles, pen work, book covers, fabrics, carpets—all caught the fever. Ottoman sources from the 18th century dubbed it saz writing, a lane all its own for illuminators and painters.

“Saz” nods to reeds or plants—sometimes a thick forest crawling with lions, dragons, Simurgh, and odd birds. Pair it with “way,” it’s a mannered dance on plain paper, ink sketching plants, and beasts, real or dreamed-up—fairies, dragons, Simurghs. Brushes twist agile lines, giving volume to figures locked in a tussle. One motif rises above the chaos, paint, and pen lifting it clear. Originality reigns—no repeats, every stroke deliberate.

Patterns in SAZ lock together. Leaves and blooms mingle with animals, painting a forest’s tale. Artists wield free brushes and are pattern-savvy, filling broad swaths. Şah Kulu’s dense, interwoven designs shine as the saz hallmark—one motif pops out, teased by a sly paint trick—gold and soot ink streak over tinted, sized paper, rare and alive.

Cordon has the saz spirit—16th-century Ottoman vegetal fire, long, feathery leaves, and mixed blossoms blazing. Şah Kulu’s reign under Suleiman birthed it; Murad III’s time—1574 to 1595—saw its peak, like in a 1572-73 album for the future sultan. After Murad’s exit in 1595, the court workshops wobbled amid a price spiral, and saz dimmed. Past 1600, it clung on, stubborn as a weed. Revival flickered in the 1630s Baghdad Kiosk tiles, the 1663 Valide Mosque kiosk woodwork, bookbindings, and endpapers—saz stuck around, leaving traces in the Aleppo Room’s decor and France’s wild 18th-century silks.

Palace walls and caftans drank deep from saz style. Çınar’s Cordon keeps kicking; a rug is alive with Ottoman legacy.